How Common are Earth-Like Planets?

In 2009 the Kepler Space Telescope was launched into space, providing scientists (for the first time ever) an opportunity to study a population of planets outside our Solar System. Kepler has detected over 3500 confirmed planets (and counting!), and from this data one can answer some fundamental questions that humans have wondered since the dawn of time. One question that has fascinated me for decades is, "Are there other Earth-like planets in the universe?"

Along with Eric Gaidos and Yanqin Wu, I calculated that roughly 6.4% of stars house an Earth-like planet. Since there are roughly 200 billion stars in our galaxy, that means that there are roughly 13 billion Earth-like planets in our galaxy! To put that in perspective since there are roughly 7 billion people living on Earth, everyone could claim roughly two Earth-like planets for themselves =P. In addition, I calculated that 66% of stars house a planet of some kind (be it Jupiter-sized, Neptune-sized, etc.), which means that if you were to pick 2 random stars in the sky, one of them is likely to have a planet orbiting around it. Check out my paper for the details!

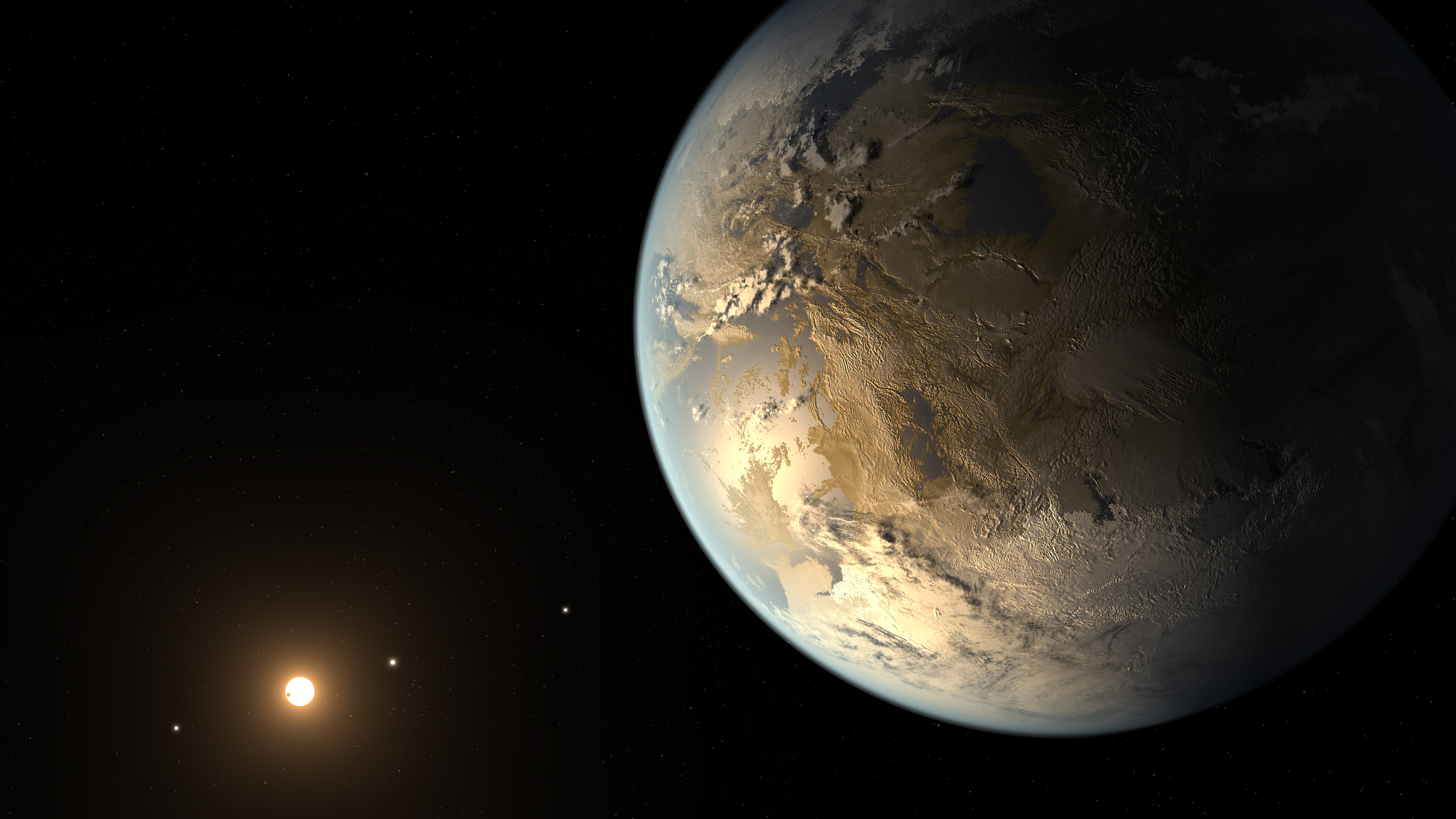

Artist impression of Kepler 186f, a potentially habitable world discovered by the Kepler Space Telescope (nasa.gov).

Artist impression of Kepler 186f, a potentially habitable world discovered by the Kepler Space Telescope (nasa.gov).

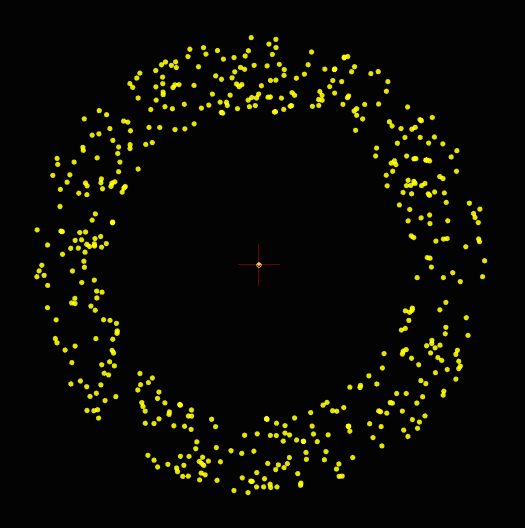

An example simulation in REBOUND consisting of a star, planet, and a disk of 500 planetesimals.

An example simulation in REBOUND consisting of a star, planet, and a disk of 500 planetesimals.